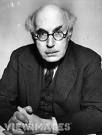

Victor Gollancz 1893 – 1967

March 20, 2009

Sir Victor

Gollancz 1893 – 1967

was a British publisher, socialist, and humanitarian.

Sir Victor

Gollancz 1893 – 1967

was a British publisher, socialist, and humanitarian.

Victor Gollancz was the publisher of Ivy Compton Burnett, and a friend of Aneurin Bevan, Richard Stafford Cripps, and Gollancz Publishers have been major publishers of homeopathic books since their inception in 1927.

Born in Maida Vale, London, Victor Gallancz was the son of a wholesale jeweller and nephew of Rabbi Professor Hermann Gollancz and Professor Israel Gollancz; after being educated at St Paul’s School, London and taking a degree in classics at New College, Oxford, he became a schoolteacher.

Gollancz was commissioned into the Northumberland Fusiliers in October 1915, although he did not see active service. In March 1916 he transferred to Repton School Junior Officers’ Training Corps. In 1917 he became involved in the Reconstruction Committee, an organization that was making plans for postwar Britain. There he met Ernest Benn, who hired him to work in the publishing business. Starting with magazines, Gollancz then brought out a series of art books, after which he started signing novelists.

Gollancz formed his own publishing company in 1927, publishing works by writers such as George Orwell and Ford Madox Ford. He was also one of the founders of the Left Book Club. He had a knack for marketing, sometimes taking out full page newspaper adverts for the books he published, a novelty at the time. He also used eye catching typography and book designs.

In addition to his highly successful publishing business, Gollancz was a prolific writer on a variety of subjects, and put his ideas into action by establishing campaigning groups. His 1943 pamphlet Let My People Go, which called for an attempt by the Allied powers to rescue Jews under threat of extermination in occupied Europe, reached a mass audience in 1943, following widespread coverage in the British media in December 1942 of the Nazi’s extermination policy.

A subsequent pamphlet, published by Gollancz later on in the war, failed to reach a mass audience. By then the British media had almost entirely ceased coverage of the story of the Nazi attempt to exterminate European Jewry, after it had become clear that the western powers were unwilling to respond to popular British sentiment at the end of 1942 and early 1943 in favour of an attempt to rescue Jews in occupied Europe, which would have meant siphoning resources from the war effort.

Along with Eleanor Rathbone, Gollancz was the the foremost British campaigner during the Second World War on the issue of the Nazi extermination of European Jewry.

After the war, he set up a campaign to send food and clothing from a Britain still subject to rationing to occupied Germany and Italy in 1945, and recruited Peggy Duff to organize it; she also worked with him on the National Campaign to Abolish Capital Punishment in the 1950s.

He received the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade in 1960, and he was knighted in 1965.

In 1945 Gollancz turned his attention to crimes against the defeated Germans. On the expulsion of Germans after World War II he said: “So far as the conscience of humanity should ever again become sensitive, will this expulsion be an undying disgrace for all those who remember it, who caused it or who put up with it. The Germans have been driven out, but not simply with an imperfection of excessive consideration, but with the highest imaginable degree of brutality.”

In his moving book, Our Threatened Values, (London, 1946) Gollancz described the conditions Sudeten German prisoners faced in a Czech concentration camp: “They live crammed together in shacks without consideration for gender and age … They ranged in age from 4 to 80. Everyone looked emaciated … the most shocking sights were the babies … nearby stood another mother with a shrivelled bundle of skin and bones in her arms … Two old women lay as if dead on two cots. Only upon closer inspection, did one discover that they were still lightly breathing. They were, like those babies, nearly dead from hunger …”

When Field Marshal Montgomery wanted to allot the Germans 1,000 calories a day and referred to the fact that the prisoners of the Bergen Belsen concentration camp had received only 800, Gollancz wrote about starvation in Germany, pointing out that many prisoners never even received 1,000 calories. “There is really only one method of re-educating people,” explained Gollancz, “namely the example that one lives oneself.”

Gollancz initiated a wave of generosity. He obtained offers of help from all over Great Britain. His campaigns and his critiques were reported in detail.

Gollancz organized a campaign for the humane treatment of German civilians and organized an airlift to provide Germany and other war torn European countries with provisions and books. “In the management of our helping actions should nothing, but absolutely nothing else, be decisive than the degree of need.”

Gollancz, together with other well known British personalities, led a massive campaign in December 1946, one and a half years after the end of the war, to persuade the British government to end the ban on sending provisions to Germany and asked that they pursue a policy of reconciliation.

In February 1951 Victor Gollancz wrote a letter to The Guardian asking people to join an international struggle against poverty. Gollancz’s, which called for a negotiated end to the Korean war and the creation of an international fund “to turn swords into ploughshares,” asked to send a postcard to Gollancz with the simple word ‘yes’. He received 5000 responses.

This directly led to the founding of international anti poverty charity War on Want In May 1951, Gollancz invited Harold Wilson to chair a committee and write a pamphlet which was eventually called ‘War on Want - a Plan for World Development’, published on 9 June 1952.