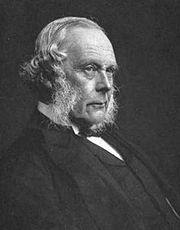

Joseph Lister 1827 – 1912

March 07, 2009

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron

Lister,

OM,

FRS 1827 –

1912 was an English surgeon who promoted the idea of sterile surgery

while working at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary.

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron

Lister,

OM,

FRS 1827 –

1912 was an English surgeon who promoted the idea of sterile surgery

while working at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary.

Joseph Lister was influenced by homeopathy, and he learnt to use aconite and belladonna from homeopaths (Dana Ullman, Discovering homeopathy: medicine for the 21st century, (North Atlantic Books, 1 Jun 1991). Page 94). Lister acknowledged that he was led to several important pharmacological discoveries due to homeopaths (Mahlon Wagner (Professor Emeritus of Psychology, State University of New York at Oswego), Victor Stenger (Professor of Physics and Astronomy, University of Hawaii), David W. Ramey, Robert H. Imrie, Homeopathy and science: a closer look, The Technology Journal of the Franklin Institute, 1999; 6(1):95-105. [http://www.colorado.edu/philosophy/vstenger/Medicine/Homeop.html](Mahlon Wagner (Professor Emeritus of Psychology, State University of New York at Oswego), Victor Stenger (Professor of Physics and Astronomy, University of Hawaii),David W. Ramey,Robert H. Imrie, HOMEOPATHY AND SCIENCE: A CLOSER LOOK, To be published in The Technology Journal of the Franklin Institute. http://www.colorado.edu/philosophy/vstenger/Medicine/Homeop.html)).

Joseph Lister taught many students who were homeopaths, including Alfred Midgley Cash (one of Joseph Lister’s dressers), Alfred Edward Hawkes, William Henderson, John Moorhead Byres Moir, Frederick Neild, William Cash Reed, Gilbert Dewitt Wilcox and many others.

Joseph Lister seemed unperturbed by his homeopathic students, probably because they were also Quakers (though not all of them were Quakers). 1854.

Edward VII, who was a close friend of homeopath Frederick Hervey Foster Quin, and who consulted homeopath John Weir, chose Lister to operate on him when he had appendicitis.

Joseph Lister challenged Louis Pasteur about his ‘attenuations’, suspecting along with everybody else that Louis Pasteur had stolen his ideas from homeopaths.

Nonetheless, Lister’s biographers still try to spin his antipathy to homeopathy, even though the motion to expell homeopaths from the Edinburgh Medical School was unsuccessful during Lister’s time. This despite the fact that Lister was married to James Syme’s daughter, as James Syme had tried unsuccessfully to expel homeopath William Henderson who was appointed Professor of General Pathology at Edinburgh University and Physician in Ordinary to the ERI in 1840.

From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Lister,_1st_Baron_Lister Joseph Lister came from a prosperous Quaker home in Upton, Essex, a son of Joseph Jackson Lister, the pioneer of the compound microscope.

At Quaker schools he became fluent in French and German which were, serendipitously, also the leading languages of medical research. He attended the University of London, one of only a few institutions which was open to Quakers at that time. He initially studied the Arts but at the age of 25 he graduated with honours as Bachelor of Medicine and entered the Royal College of Surgeons.

In 1854, Lister became both first assistant to and friend of surgeon James Syme at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

In 1867 Joseph discovered the use of carbolic acid as an antiseptic, such that it became the first widely used antiseptic in surgery. He subsequently left the Quakers, joined the Scottish Episcopal Church and eventually married James Syme’s daughter Agnes. For their honeymoon they spent 3 months visiting leading medical centres (Hospitals and Universities) in France and Germany, by this time Agnes was enamoured of medical research and partnered him in the laboratory for the rest of her life.

After six years he earned a professorship of surgery at the University of Glasgow. At the time the usual explanation for wound infection was that the exposed tissues were damaged by chemicals in the air or via a stinking “miasma” in the air. The sick wards actually smelled bad, not due to a “miasma” but due to the rotting of wounds.

Hospital wards were occasionally aired out at midday, but Florence Nightingale’s doctrine of fresh air was still seen as science fiction. Facilities for washing hands or the patient’s wounds did not exist and it was even considered unnecessary for the surgeon to wash his hands before he saw a patient.

The work of Ignaz Semmelweis and Oliver Wendell Holmes were not heeded.

Lister became aware of a paper published (in French) by the French chemist Louis Pasteur which showed that rotting and fermentation could occur without any oxygen if micro organisms were present. Lister confirmed this with his own experiments. If micro-organisms were causing gangrene, the problem was how to get rid of them. Louis Pasteur suggested three methods: filter, heat, or expose them to chemical solutions. The first two were inappropriate in a human wound, so Lister experimented with the third.

Carbolic acid (phenol) had been in use as a means of deodorizing sewage, so Lister tested the results of spraying instruments, the surgical incisions, and dressings with a solution of it. Lister found that carbolic acid solution swabbed on wounds markedly reduced the incidence of gangrene and subsequently published a series of articles on the Antiseptic Principle of the Practice of Surgery describing this procedure in Volume 90, Issue 2299 of The Lancet published on 21 September 1867.

He also made surgeons wear clean gloves and wash their hands before and after operations with 5% carbolic acid solutions. Instruments were also washed in the same solution and assistants sprayed the solution in the operating theatre. One of his conclusions was to stop using porous natural materials in manufacturing the handles of medical instruments.

Lister left Glasgow in 1869, returning to Edinburgh as successor to Syme as Professor of Surgery at the University of Edinburgh, and continued to develop improved methods of antisepsis and asepsis. His fame had spread by then and audiences of 400 often came to hear him lecture.

As the germ theory of disease became more widely accepted, it was realised that infection could be better avoided by preventing bacteria from getting into wounds in the first place. This led to the rise of sterile surgery. Some consider Lister “the father of modern antisepsis.”

In 1879 Listerine mouthwash was named after him for his work in antisepsis. Also named in his honour is the bacterial genus Listeria, typified by the food borne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes.

Lister moved from Scotland to King’s College Hospital, in London, and became the second man in England to operate on a brain tumor. He also developed a method of repairing kneecaps with metal wire and improved the technique of mastectomy. His discoveries were greatly praised and he was made Baron Lister of Lyme Regis in 1897 and became one of the twelve original members of the Order of Merit and a Privy Councillor in the Coronation Honours in 1902.

Among his students at King’s College London was Robert Hamilton Russell who later moved to Australia.

In life Lister was said to be a shy, unassuming man, deeply religious in his beliefs, and uninterested in social success or financial gain.

Lister retired from practice after his wife, who had long helped him in research, died in 1893 in Italy, during one of the few holidays they allowed themselves. Studying and writing lost appeal for him and he sank into religious melancholy.

Despite suffering a stroke, he still came into the public light from time to time. Edward VII came down with appendicitis two days before his coronation. The surgeons did not dare operate without consulting Britain’s leading surgical authority. Edward VII later told Lister “I know that if it had not been for you and your work, I wouldn’t be sitting here today”.

Lister died on 10 February 1912 at his country home in Walmer, Kent at the age of 84. After a funeral service at Westminster Abbey, he was buried at Hampstead Cemetery, Fortune Green, London in a plot to the south west of central chapel.