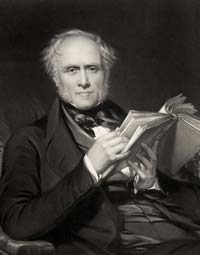

John Forbes 1787 - 1861

December 10, 2008

John

Forbes 1787

John

Forbes 1787

- 1861 physician and medical journalist, and one of the founders of the British Medical Association alongside John Conolly and Charles Hastings. He was physician to Queen Victoria 1841–1861.

John Forbes was one of the very few orthodox physicians who gave earnest consideration to homeopathy, despite vicious attacks from his colleagues for doing so. Forbes attacked and defended homeopathy, but he did remain unbiased and even handed, and so he remains a shining light in medical journalism and a rare creature indeed.

(See Anon, *The Lancet London: *A Journal of British and Foreign Medicine, Surgery, Obstetrics, Physiology, Chemistry, Pharmacology, Public Health and News, Volume 1. (Elsevier, 1857). Page 648. Remarkable that _The Lancet actually recommended homeopathy __to a correspondent called WPK who was suffering from hay fever, _via a private note to Dr. Forbes for homeopathic advice!)

John Forbes said ‘… It is utterly impossible to disregard the claims of homeopathy as an established form of practical medicine, as a great fact in the history of our art; we cannot ignore it…’ ‘…for not only do we see all our ordinary diseases cured homeopathically, but even all the severer and more dangerous diseases which demand by the common method prompt and strong measures to prevent a fatal issue…’ (Homeopathic Record Volume 1. 1855. _London Tweedie 337 Strand, Northampton J Parton Berry Corn Exchange Parade 1856. Page 89 onwards). _

John Forbes was a student of homeopath Friedrich Wilhelm Karl Fleischman, and he was the physician to the household of Queen Victoria from 1840, a friend of Prince Albert, James Clark, William Henderson, Florence Nightingale, John Ozanne, Robert Peel, David Wilson, and many others.

Forbes argued publically with homeopath William Henderson, but Forbes came out to defend homeopath John Ozanne, when both Forbes and William Henderson came to give evidence for John Ozanne’s defence, where Forbes declared that it was ’but simple justice to admit that Hahnemann was a man of profound learning and perfect integrity, and that many of his disciples were sincere, honest and learned men‘.

Forbes was responsible for the conversion to homeopathy of David Wilson, who was a severe skeptic against homeopathy who wrote to the Lancet to contribute an article called grandmother meddlesome. David Wilson explains that his conversion to homeopathy was due to John Forbes, the editor of The British and Foreign Medical Review and Physician to the Queen’s Household, who was himself converted by William Henderson of Edinburgh, Physician of the Royal Infirmary who wrote a book on homeopathy which David Wilson read.

In 1839, Lady Shrewsbury (daughter of John Talbot 16th Earl of Shrewsbury) married Philip Andrew Doria Pamphili Landi, an Italian Prince, who brought his Body Physician Francesco Romani with him back to England.

Francesco Romani opened a homeopathic clinic at Alton Towers in 1839, where he was assisted by Daniells and Roch. To begin with, The British and Foreign Review edited by John Forbes mentioned this clinic in ’most flattering terms’, but it soon changed its tone. Queen Adelaide had given up her allopathic physician who could not help her, to patronise John Ernst Stapf, who attended Queen Adelaide in Nuremberg and saved her life after her allopathic physicians had given up on her.

The ‘Mansions of the Nobility’ opened up to homeopathy as a result. (no doubt John Forbes was under some attack from allopaths for his ’most flattering terms’, and was forced to change tack - though it is also possible that anti Catholic sentiment played a part as John Talbot 16th Earl of Shrewsbury was the acknowledged lay leader of English Catholicism).

In 1846, an allopathic doctor, George William Balfour of Edinburgh, studied for three months with Friedrich Wilhelm Karl Fleischman at the Vienna Homeopathic Hospital, on the insistence of John Forbes, to observe the homeopathic treatment of his patients, and who made extensive reports of his findings there to John Forbes. (_Report on the Homeopathic Treatment of Acute Diseases in Dr. Fleischmann’s Hospital, Vienna, during the months of May, June and july 1846_) (John Forbes Homeopathy, allopathy and ‘young physic British and Foreign Medical Review 21:225-265 1846).

With thanks to Robin Agnew and the James Lind Library: John Forbes was born on 17 December 1787 at Cuttlebrae, near Cullen, in the parish of Rathven, Banffshire, on the Moray Firth in North-East Scotland. He was the fourth son of a local tenant farmer, Alexander Forbes and Cicilia Wilkie. The family later moved to Dytac (or Dytach) in the parish of Fordyce, a few miles from Cullen and close to the coast at Sandend Bay, where young John learned to swim in the cold waters of the North Sea.

With his friend James Clark, who also came of farming stock, he walked to the local parish school at Fordyce. They became close friends and their later medical careers coincided as physicians in London… At the age of fifteen John Forbes joined the Rector’s class at Aberdeen Grammar School, where he expanded his knowledge of Mathematics, English, French, Dutch and the Classics, the rudiments of which he had learned at Fordyce.

He next entered the Arts course of Marischal College, Aberdeen, where he attended classes between 1803 and 1805 but there is no record that he ever graduated BA from the University…

John Forbes’ naval career coincided with the latter part of the Napoleonic Wars and, apart from a short period of retraining in naval medicine and surgery at the Royal Hospital Haslar in 1811, he spent his time at sea. He was confirmed in the rank of full surgeon on 27 January 1809…

John Forbes enrolled in the flourishing medical school at Edinburgh in 1816, as a 29-year-old mature student. He worked hard. His Latin dissertation, which he dedicated to his naval mentor Philip Durham, was accepted within a year, and he proceeded MD (Edin.) in August 1817, on the same day as his friend James Clark.

During the course of his medical studies Forbes had attended lectures in geology given by Professor Robert Jamieson. The professor was asked to recommend an Edinburgh physician with an interest in geology for a medical practice in Penzance, Cornwall. Forbes was duly recommended and appointed, and he moved to Penzance in September 1817. His duties involved both general medical practice and as physician to the Penzance Public Dispensary.

Between 1817 and 1822 he laid the foundations for his knowledge of the newly invented stethoscope of Rene Laennec, an early model of which James Clark had brought back from Paris in 1818. James Clark was enthusiastic about the French physician’s teaching on stethoscopy as expressed in his classical work_ De L’Auscultation Médiate_ (1819), and, prompted by James Clark, Forbes translated this into English in four editions issued between 1821 and 1834.

His first translation A Treatise on Diseases of the Chest (1821) was a great success and was instrumental in spreading Rene Laennec’s teachings to the English speaking world.

On 19 May 1820, Forbes married Eliza Mary Burgh (1787-1851) at Great Torrington, Devon.

He took a keen interest in local Cornish academic activities, contributing papers to the Royal Geological Society of Cornwall, of which he was secretary. One of his best papers drew attention to the health of Cornish tin and copper miners, including pioneer studies of their working conditions and the stethoscopic signs of pulmonary tuberculosis.

He addressed the Penwith Agricultural Society on local natural history and climate, noting its benefits for convalescent patients. Remarkably, he found the time to be the first honorary Librarian of Penzance Public Library, which he had helped to found in 1818. These achievements, together with his translations and later practical use of the stethoscope in Chichester, were recognized when he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1829…

At Chichester, Forbes wrote his major innovative medical work Original Cases with Dissections and Observations illustrating the use of the Stethoscope and Percussion in the diagnosis of Diseases of the Chest (1824). This included the first English translation of the Austrian physician Auenbrugger’s (1722-1809) new technique of percussion of the chest wall. Forbes described thirty nine patients, treated by him at Chichester, in whom the vital physical signs were verified by autopsy in fatal cases. This was another importation of Rene Laennec’s doctrines into British practice…

Forbes successfully combined private medical practice with his hospital work at the new Chichester Infirmary over fourteen years…

A potential rival, John Conolly, also an Edinburgh graduate, departed amicably in order to pursue a career elsewhere. They remained good friends and, in collaboration with a third Edinburgh graduate, Alexander Tweedie (1794-1884), they launched a Cyclopaedia of Practical Medicine in four volumes (Forbes et al. 1832-35).

This was John Forbes’ first venture into medical journalism, a new career which was to engage his faculties over the next fifteen years. In addition to contributing his own articles to the Cyclopaedia, he was also its main editor. His creation of a Manual of Select Medical Bibliography (Forbes 1835) was a yardstick of excellence and also made up for the absence of references in the original articles in the Cyclopaedia. The Cyclopaedia was a popular forum for the best medical writers in the British Isles and made a handsome profit when it was sold in 1835.

In 1836, Forbes and John Conolly started a new publication in 1836: the_ British and Foreign Medical Review, or, _A Quarterly Journal of Practical Medicine. They shared the editorship from 1836 to 1839, when John Conolly resigned to work full time in psychiatry. The British and Foreign Medical Review was read widely in Europe and America, its articles helping to promote modern methods of diagnosis and treatment and enhancing the reputation of British medicine.

During the late 1830’s, Forbes continued working in his busy clinical practice in Chichester but still kept up his interests outside medicine. His Lecture on poetry and fiction considered as sources of pleasure and improvement was printed privately in 1837. He dedicated it to his elder brother, Alexander, who had emigrated to Tepic in Mexico some years previously…

On 15 October 1840, John Forbes resigned as senior physician at Chichester Infirmary in order to take up residence at 12 Old Burlington Street, Westminster. This move was to prove a turning point in his career and an anxious time for his wife and 18 year old son.

Fortunately, he was helped by James Clark, his friend from schooldays in Fordyce. By this time, James Clark had been created a baronet for his services to the young Queen Victoria, who had succeeded to the throne in 1837. On 15 February 1841, Forbes was appointed court physician to Prince Albert, and the royal household.

The Scottish physician had now reached the peak of his medical and journalistic careers. Further honours followed: Fellowship of the Royal College of Physicians was conferred on him in 1844 and honorary fellowship of the Imperial Society of Physicians in Vienna in 1845.

The British and Foreign Medical Review established his reputation in medical journalism and helped in building up his consultant practice in London. Unfortunately, the success of these years was marred by the chronic ill health of his wife Eliza, who died in 1851.

His interests outside conventional medicine extended to include such esoteric subjects as animal magnetism, which were based on the ideas of the Austrian physician Franz Anton Mesmer, who claimed to cure diseases in seances but was exposed as an imposter by a royal commission in 1784. Similarly, Forbes had published an article on ‘Sleepwalking, clairvoyance and animal magnetism’, written in German and published in Vienna (Forbes 1846).

In the previous year, he had ridiculed clairvoyance in an article that had appeared in a London literary journal (Forbes 1845) and was congratulated by a reviewer for his patience in trying to establish whether the demonstrations of clairvoyance and mesmerism were genuine or fraudulent by personally witnessing them.

In addition, Forbes was interested in phrenology and homeopathy, which fuelled the flames of professional jealousy in some of his medical colleagues.

In January 1846, he published anonymously in the British and Foreign Medical Review a commentary entitled Homeopathy, allopathy and young physic. This drew on nine British and foreign authors on homeopathy, including three by its founder, Samuel Hahnemann, and one by a doctor at Forbes’ alma mater in Edinburgh…

It opens by remarking that the subject of homeopathy had never been formally addressed in the Review and admits that, by comparison with “every country in Europe”, it had been neglected in Britain as a system of medical doctrine and practice.

As indicated by the title of his article, Forbes broadened his approach to the subject by extending it beyond homeopathy to include an examination of the evidential basis for contemporary mainstream medicine.

He was firmly of the opinion that drugs were often prescribed prematurely and in too large amounts without waiting to see whether masterly inactivity (the vis medicatrix naturae) would be effective.

He felt that this dictum applied particularly in the case of young, inexperienced doctors, fresh out of medical school, where passing final qualifying examinations had depended on unquestioning obedience to the dictates of their professors.

He concluded that the practice of medicine should be based on a combination of art and science and that this could only be done by improving standards of medical education. It is clear to anyone who takes the trouble to read the forty pages of the article that Forbes, as an impartial editor, kept an open mind on Samuel Hahnemann’s ‘like cures like’, but that he had no time for medical quackery, whether promulgated by unorthodox practitioners or by mainstream doctors.

In his later little philosophical book Of Nature and Art in the Cure of Disease (Forbes 1857), Forbes goes as far as to say that “a large proportion of cases of disease [which] recover under homeopathy…recover by means of the curative powers of Nature alone.”

He concluded that homeopathy is “one of the greatest delusions…of the healing art” and the only good that ensues from its practice is the reduction in “the monstrous polypharmacy which has always been the disgrace of our art – by at once diminishing the frequency of administration of drugs and lessening their dose.” (Chapter VII, pp 162-63).

In spite of Forbes’ even handed approach, the London medical establishment considered his views iconoclastic and this view of Forbes persisted in some circles, as was reflected in an unflattering obituary notice which appeared in The Lancet nearly sixteen years later, which referred to the Scottish physician’s “obnoxious articles” published in the British and Foreign Medical Review (Anon 1861).

An article entitled Medical Errors written by a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of London (Barclay 1864, pp 3-4) questioned Forbes’ claim that Nature was often the chief cause of success in the treatment of disease, as opposed to the ‘inductive logic’ that guided Barclay’s own therapeutic philosophy.

This curt dismissal of Forbes’ dictum ignores the main thrust of his sensible approach to therapeutics, namely, that too many drugs administered too often may have a disastrous effect on prognosis.

It must be remembered that, at the time that Barclay and others were expressing these views, specific remedies for most diseases did not exist, although the medical world stood on the brink of basic scientific discoveries in microbiology.

Historical evidence from the epidemic of yellow fever in the West Indies a half century previously supports Forbes’ conservative approach: in contrast to the reliance of British doctors on bleeding and purging, the French method was to ‘let nature take its course’ and to give their patients symptomatic relief and ‘careful nursing’ (Brockliss et al. 2005, p 54).

John Forbes’ general reputation was unharmed, however, as, in 1846, he was appointed as one of the first two consulting physicians to the Brompton Hospital for Consumption and Diseases of the Chest. He resigned as editor of the British and Foreign Medical Review _in 1847, unrepentant for challenging the medical establishment. This may, in part, have resulted in his journal’s commercial failure and in its subsequent amalgamation with Johnson’s _Medico-Chirurgical Review _ in 1848, to form the _British and Foreign Medico-Chirurgical Review.

Further evidence that Forbes’ reputation as an unbiased editor and of his integrity as a physician were unharmed by his challenge to orthodox medicine is provided by the fact that, in 1858, one of his colleagues at the Brompton Hospital dedicated a textbook on pulmonary tuberculosis to him.

The author describes Forbes as “one who, through his long life, has exerted no inconsiderable influence over his profession, and who, amongst his other distinguishing qualities, has had the courage to question the groundwork of some of the principles of his art, and with a view to their correction has boldly expressed his convictions” (Smith 1858)…

In the Introduction to Of Nature and Art in the Cure of Disease, _Forbes writes (p vi): “It is my intention, on some future occasion, to publish another volume of the same size as the present, consisting of the original article _Homeopathy, allopathy and ‘young physic_ _written by me (my italics),in 1845, together with a selection from the correspondence elicited by it, at the time, from my medical friends.

The first of these papers will be found in No. XLI of the ‘British and Foreign Medical Review’ (then edited by me), and the remainder in the subsequent numbers of the same journal. This additional volume, though it will afford considerable support to the author’s views as promulgated in the present work, will still leave the subject in a very incomplete state.” LONDON, February 1st 1857. (Forbes 1857).

In the first chapter in Of Nature and Art in the Cure of Disease Forbes explains his reasons for writing the book, and this makes clear that his views had changed from scepticism to outright condemnation of the unorthodox doctrines of mesmerism and homeopathy, while still advocating the benefits of the curative properties of Nature and medical “secundum artem” (Forbes 1857, pp 11-16).

Unfortunately, ill health prevented the appearance of an “additional volume” on the vis medicatrix naturae, but I strongly recommend reading the original. A signed copy, presented by Forbes, is in the library of the Royal College of Physicians of London… continue reading: