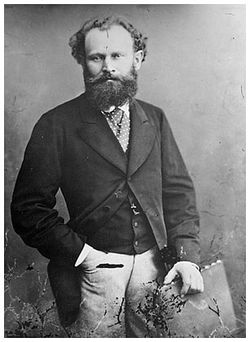

Edouard Manet 1832 – 1883

September 24, 2008

Edouard

Manet 1832 – 1883

was a French painter. One of the first nineteenth century artists to

approach modern life subjects, he was a pivotal figure in the transition

from Realism to

Impressionism.

Edouard

Manet 1832 – 1883

was a French painter. One of the first nineteenth century artists to

approach modern life subjects, he was a pivotal figure in the transition

from Realism to

Impressionism.

Manet consulted homeopath Paul Ferdinand Gachet and he also consulted homeopath Georges de Bellio, who often bought paintings from the impoverished artist in the early days (Dana Ullman, The Homeopathic Revolution: Why Famous People and Cultural Heroes Choose Homeopathy, (North Atlantic Books, 2007). Page 176. See also Édouard Manet, Françoise Cachin, Michel Melot, Charles S. Moffet, Juliet Wilson Bareau, Manet, 1832-1833: Galeries Nationales Du Gran Palais, Paris, April 22-August 8, 1983,the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, September 10-November 27, 1983, (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1983). Page 368).

It was Georges de Bellio who attended Manet in his final illness.

Camille Pissarro complained in a letter to his son Lucien ‘… Our poor friend Manet is terribly sick. He has been completely poisoned by allopathic medicine…’ (Camille Pissarro, Lucien Pissarro, Camille Pissarro: letters to his son Lucien, (Pantheon Books inc., 1943). Page 25).

From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89douard_Manet Edouard Manet was born in Paris on January 23, 1832, to an affluent and well connected family. His mother, Eugénie Desirée Fournier, was the daughter of a diplomat and the goddaughter of the Swedish crown prince, Charles Bernadotte, from whom the current Swedish monarchs are descended.

His father, Auguste Manet, was a French judge who expected Édouard to pursue a career in law. His uncle, Charles Fournier, encouraged him to pursue painting and often took young Manet to the Louvre.

In 1845, following the advice of his uncle, Manet enrolled in a special course of drawing where he met Antonin Proust, future Minister of Fine Arts, and a subsequent life long friend.

At his father’s suggestion, in 1848 he sailed on a training vessel to Rio de Janeiro. After twice failing the examination to join the navy, the elder Manet relented to his son’s wishes to pursue an art education.

From 1850 to 1856, Manet studied under the academic painter Thomas Couture, a painter of large historical paintings. In his spare time he copied the old masters in the Louvre.

From 1853 to 1856 he visited Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands, during which time he absorbed the influences of the Dutch painter Frans Hals, and the Spanish artists Diego Velázquez and Francisco José de Goya.

In 1856, he opened his own studio. His style in this period was characterized by loose brush strokes, simplification of details, and the suppression of transitional tones. Adopting the current style of realism initiated by Gustave Courbet, he painted The Absinthe Drinker (1858-59) and other contemporary subjects such as beggars, singers, Gypsies, people in cafés, and bullfights.

After his early years, he rarely painted religious, mythological, or historical subjects; examples include his Christ Mocked, now in the Art Institute of Chicago, and Christ with Angels, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York…

He became friends with the Impressionists Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Pierre Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Paul Cezanne, and Camille Pissarro, through another painter, Berthe Morisot, who was a member of the group and drew him into their activities. The grand niece of the painter Jean Honoré Fragonard, Berthe Morisot’s paintings first had been accepted in the Salon de Paris in 1864 and she continued to show in the salon for ten years.

Manet became the friend and colleague of Berthe Morisot in 1868. She is credited with convincing Manet to attempt plein air painting, which she had been practicing since she had been introduced to it by another friend of hers, Camille Corot. They had a reciprocating relationship and Manet incorporated some of her techniques into his paintings. In 1874, she became his sister in law when she married his brother, Eugene.

Unlike the core Impressionist group, Manet maintained that modern artists should seek to exhibit at the Paris Salon rather than abandon it in favor of independent exhibitions. Nevertheless, when Manet was excluded from the International exhibition of 1867, he set up his own exhibition. His mother worried that he would waste all his inheritance on this project, which was enormously expensive. While the exhibition earned poor reviews from the major critics, it also provided his first contacts with several future Impressionist painters, including Edgar Degas.

Although his own work influenced and anticipated the Impressionist style, he resisted involvement in Impressionist exhibitions, partly because he did not wish to be seen as the representative of a group identity, and partly because he preferred to exhibit at the Salon. Eva Gonzalès was his only formal student.

He was influenced by the Impressionists, especially Claude Monet and Berthe Morisot. Their influence is seen in Manet’s use of lighter colors, but he retained his distinctive use of black, uncharacteristic of Impressionist painting. He painted many outdoor (plein air) pieces, but always returned to what he considered the serious work of the studio.

Manet enjoyed a close friendship with composer Emmanuel Chabrier, painting two portraits of him; the musician owned 14 of Manet’s paintings and dedicated his Impromptu to Manet’s wife.

Throughout his life, although resisted by art critics, Manet could number as his champions Emile Zola, who supported him publicly in the press, Stephane Mallarme, and Charles Pierre Baudelaire, who challenged him to depict life as it was. Manet, in turn, drew or painted each of them…

In January 1871 Manet traveled to Oloron-Sainte-Marie in the Pyrenees. In his absence his friends added his name to the “Fédération des artistes” (see:Courbet) of the Paris Commune. Manet stayed away from Paris, perhaps, until after the semaine sanglante. In a letter to Berthe Morisot at Cherbourg (June 10, 1871) he writes :” We came back to Paris a few days ago…”.(the semaine sanglante ended on 28 May)…

On 18 March 1871 he wrote to his (confederate) friend Felix Bracquemond in Paris about his visit to Bordeaux, the provisory seat of the French National Assembly of the Third French Republic where Emile Zola introduced him to the sites: ” I never imagined that France could be represented by such doddering old fools, not excepting that little twit Thiers…” (There followed some colorful language unsuitable at social events. See “Manet by himself” 1991/2004.)

If this could be interpreted as support of the Commune a following letter to Félix Bracquemond (March 21, 1871) expressed his idea more clearly: “Only party hacks and the ambitious, the Henrys of this world following on the heels of the Milliéres, the grotesque imitators of the Commune of 1793…”

He knew the communard Lucien Henry to have been a former painters model and Millière, an insurance agent. “What an encouragement all these bloodthirsty caperings are for the arts! But there is at least one consolation in our misfortunes: that we’re not politicians and have no desire to be elected as deputies”…

In 1863 Manet married Suzanne Leenhoff, a Dutch-born piano teacher of his own age with whom he had been romantically involved for approximately ten years. Leenhoff initially had been employed by Manet’s father, Auguste, to teach Manet and his younger brother piano. She also may have been Auguste’s mistress.

In 1852, Leenhoff gave birth, out of wedlock, to a son, Leon Koella Leenhoff.

After the death of his father in 1862, Manet married Suzanne. Eleven year old Leon Leenhoff, whose father may have been either of the Manets, posed often for Manet. Most famously, he is the subject of the Boy Carrying a Sword of 1861 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). He also appears as the boy carrying a tray in the background of The Balcony…

Manet died of untreated syphilis and rheumatism, which he contracted in his forties. The disease caused him considerable pain and partial paralysis from locomotor ataxia in the years prior to his death.

His left foot was amputated because of gangrene, an operation followed eleven days later by his death. He died at the age of fifty-one in Paris in 1883, and is buried in the Cimetière de Passy in the city.

[In 1879, Jonathan Hutchinson delivered a speech on syphilis to the British Medical Association. He dubbed the disease the Great Imitator for its propensity to mimic the symptoms of many other diseases](http://64.233.183.104/search?q=cache:BcLANWB-aMEJ:www.blreview.org/issue_fall2005/the%2520great%2520imitator.pdf+Manet+homeopath&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=2&gl=uk&client=firefox-a), including smallpox, psoriasis, lupus, and epilepsy....

I am a disease. My very existence poisons my father’s life. The circumstances of my birth are as unspeakable as the name of the affliction that is slowly eroding his body.

Look at how Manet, this man that I have been taught to call my godfather, my parain, cringes as I help him with his stylish dress. I reach my arms about him to tie his cravat, and he shrinks away from my almost embrace…

Like Manet, most of the diseased lean heavily on canes…

The Judge, Manet’s father, ended like these old men, angry and insane. His family propped him up in a chair with his red ribbon of the Legion of Honor pinned to his chest, and for twelve years,

Manet used this incontinent puppet’s displeasure as an excuse to not marry my “sister” Suzanne… Is mad Auguste still clenching his jaw in that censorious manner in his grave, thinking of his son’s marriage to this commoner? Or does his skull smile with the knowledge that when Suzanne and the artist finally married, I was eleven years old, too old to be legitimized without setting tongues wagging?…

In his paintings, my parain has twice cast me as a serving boy. He assigns me an equally servile role in his life. Consequently, I am the one to accompany him to the homeopath who prescribes the ergot. I am the one to mix up the nasty stuff, a fungus that smells like rye bread and dusty feet, and I am the one to feed it to him…